From the Gartner Hype Cycle to the Dunning-Kruger Effect in Technical Development

During my tenure as Enterprise Architect at Methanex, the world’s largest methanol producer, I relied heavily on resources like the Gartner Hype Cycle to monitor emerging technologies that could provide a competitive advantage to our company. With a subscription to the Gartner Group, I observed how innovations often followed predictable patterns of inflated expectations and subsequent disillusionment before reaching maturity. At the time, I focused on applying this knowledge to strategic technology adoption, but over the years, I’ve come to realize how interconnected these concepts are with broader psychological and cognitive frameworks, like the Dunning-Kruger effect and the nature of technical knowledge.

Understanding the Gartner Hype Cycle

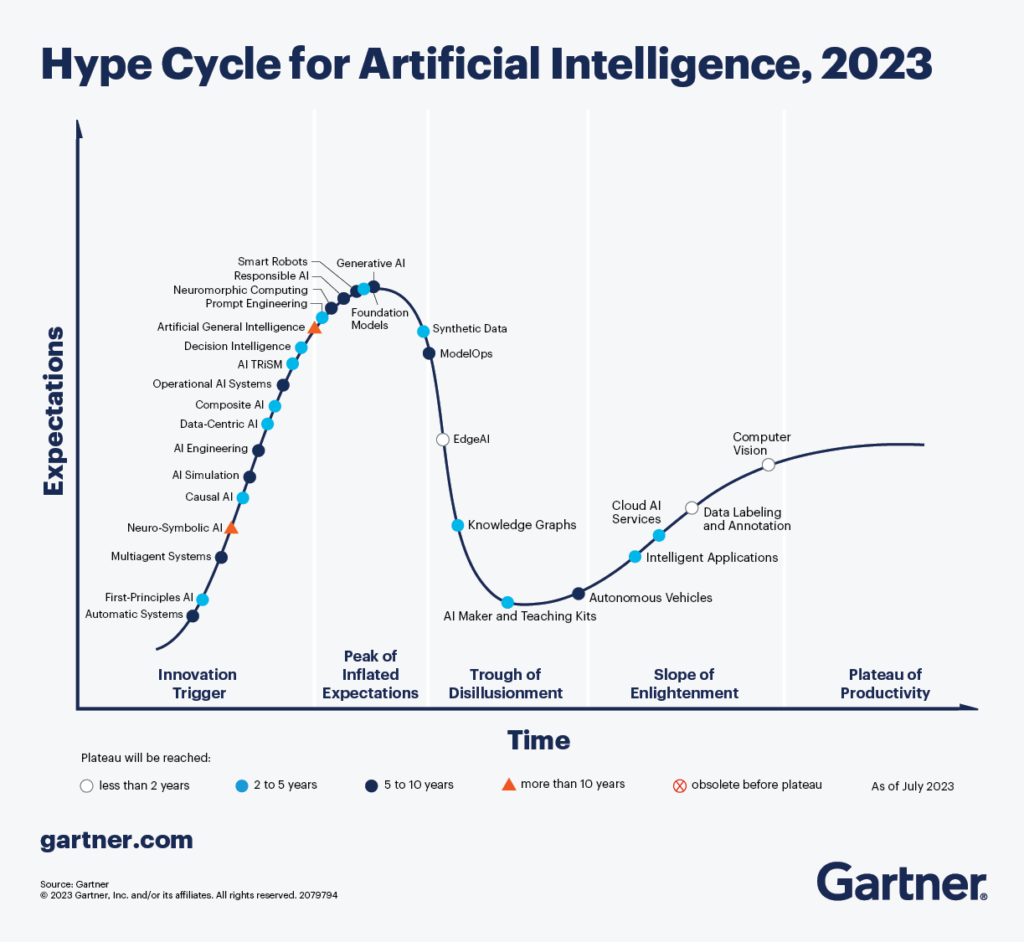

The Gartner Hype Cycle provides a clear roadmap for how technologies evolve, moving through stages such as:

- The Peak of Inflated Expectations, where initial excitement and hype lead to unrealistic optimism.

- The Trough of Disillusionment, as reality sets in, and inflated expectations give way to a more sober view of the technology’s limitations.

- The Slope of Enlightenment, where real, practical applications emerge.

- The Plateau of Productivity, where widespread adoption and tangible benefits become apparent.

For a technology-driven organization like Methanex, keeping an eye on these trends allowed us to understand not just when to adopt, but also when to avoid getting caught up in the hype of emerging trends that hadn’t yet proven themselves.

Here is an example of the Hype Cycle for AI, note how much hype there was back in 2023 around AI technologies and just a few were past the Trough of Disillusionment.

Without looking at the updated chart for 2024, I would dare to guess that technologies such as Generative AI and LLMs are moving quickly through the chart and would be in the process of moving out of the Through of Disillusionment into the Slope of Enlightment.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect: The Psychology of Overconfidence

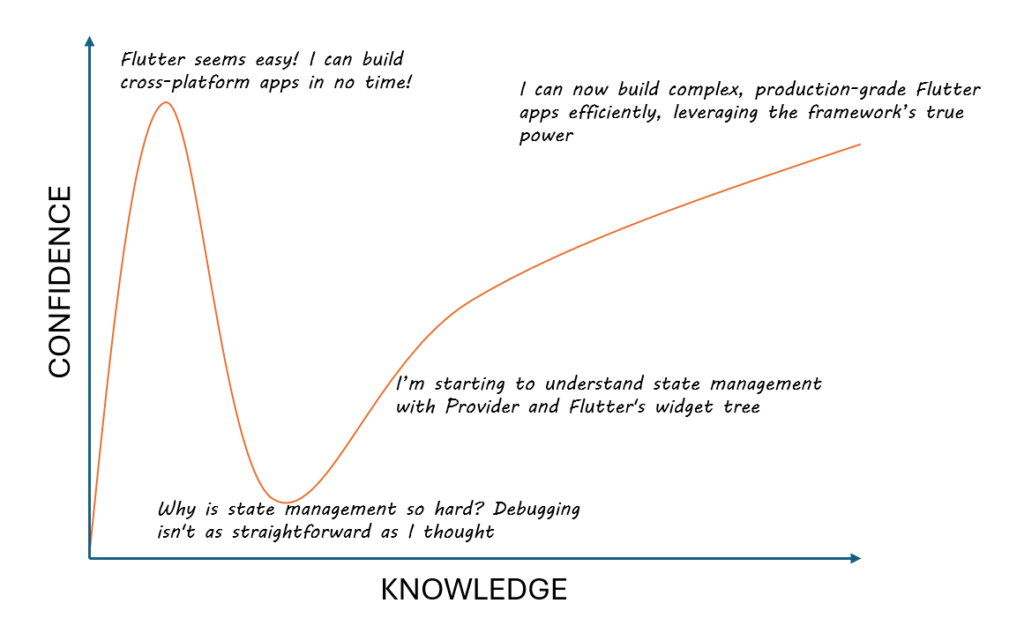

Years later, as I reflected on my experience with technology adoption and monitoring trends, I became more aware of the Dunning-Kruger effect, a cognitive bias that explains why people with limited knowledge or expertise tend to overestimate their abilities. This effect outlines a familiar journey:

- Overconfidence at the start: When someone begins learning a new skill or concept, they often feel more confident than they should, not yet aware of the complexities they don’t understand. This overconfidence mirrors the Peak of Inflated Expectations in the Hype Cycle.

- Realization of ignorance: As they continue learning, they encounter complexities they hadn’t anticipated, leading to a dip in confidence. This parallels the Trough of Disillusionment.

- Gradual increase in competence: Finally, through persistent effort, real competence is gained, which aligns with the Slope of Enlightenment and Plateau of Productivity in the Hype Cycle.

The similarity between these models of technological and personal development is striking. Just as organizations misjudge technologies in the Gartner Hype Cycle, individuals misjudge their own competence according to the Dunning-Kruger effect. In both cases, the journey leads from unrealistic optimism to sober understanding and, eventually, productive mastery.

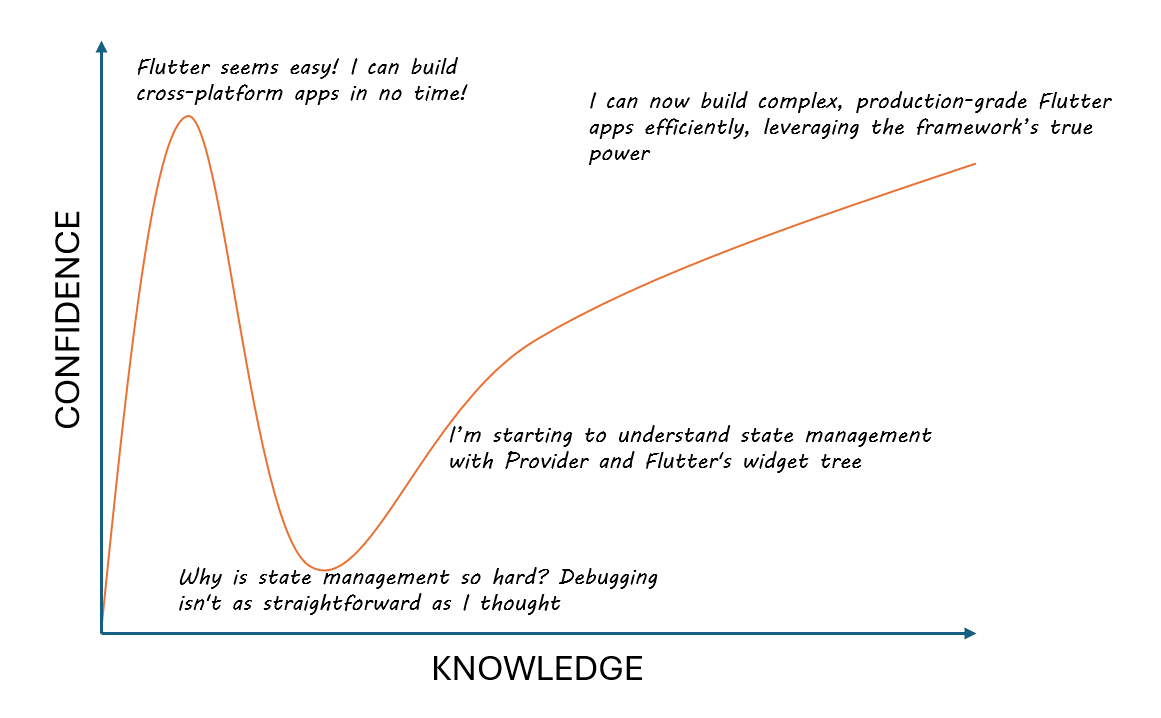

To illustrate the DK Effect, here is an example of my journey developing Flutter apps for iOS, Android and Web last year:

The Pyramid of Knowledge: What You Know and Don’t Know

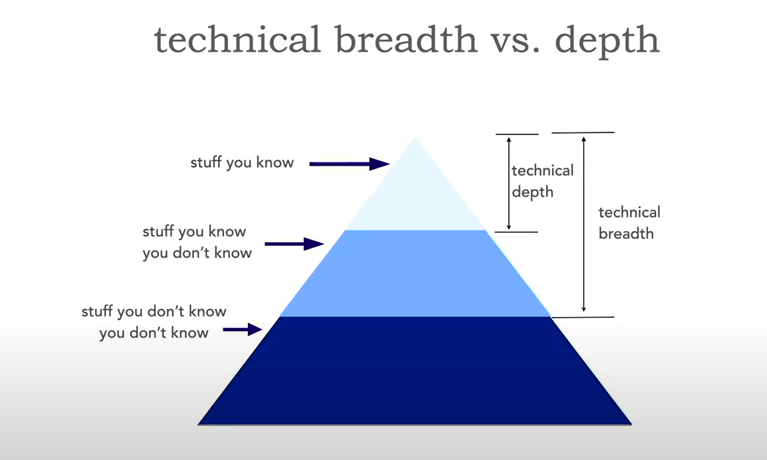

A third element that I’ve come to appreciate more over time is the pyramid of knowledge, which categorizes what we know into three layers:

- Stuff you know: Your area of expertise or established knowledge.

- Stuff you know you don’t know: Topics you’re aware of but haven’t mastered.

- Stuff you don’t know you don’t know: The most challenging category, representing blind spots or areas of ignorance.

Credit: Mark Richards

This pyramid also applies to both individuals and organizations as they navigate new technologies and trends. Early on, much of what seems straightforward falls into the “stuff you know” category. But as you dive deeper, the “stuff you know you don’t know” becomes clearer, and blind spots emerge—the “stuff you don’t know you don’t know.” This is where significant breakthroughs or setbacks can happen.

This pyramid can also relate to the T-shaped skills concept, where individuals build a broad understanding across many fields (breadth) while developing deep expertise in one area (depth). In a business context, understanding this balance helps teams and leaders navigate both familiar and unknown territories, ensuring that they are not blindsided by the complexities of new technologies or trends.

Tying It All Together

Reflecting on my experience at Methanex and beyond, I now see how the Gartner Hype Cycle, Dunning-Kruger effect, and the pyramid of knowledge are all connected in the process of learning and technology adoption. Whether it’s an individual overestimating their own skills or a business overhyping a new technology, the cycle of overconfidence, disillusionment, and eventual mastery is universal.

At Methanex, the Gartner Hype Cycle gave us the tools to make informed decisions on when to adopt or dismiss technologies, but it also taught a valuable lesson about the human tendency to oversimplify and overestimate our understanding. Over time, I’ve come to see that success in technology management isn’t just about identifying the right tools or trends, but about recognizing what you don’t know and navigating that journey from overconfidence to competence.

By understanding these interconnected frameworks, both individuals and organizations can better prepare for the inevitable ups and downs of learning, adoption, and implementation, whether in new technologies or in personal development.

Conclusion

In today’s fast-paced technology environment, the lessons of the Gartner Hype Cycle, Dunning-Kruger effect, and technical depth vs. breadth are more relevant than ever. Recognizing these patterns helps us avoid the pitfalls of overconfidence, manage the complexities of learning, and ultimately, achieve long-term success—whether we are evaluating new technologies for a company or honing our own skills.

As Socrates once said:

“The only true wisdom is knowing you know nothing.”